NRECA International training program works to equip Ugandan co-ops for success

Originally published in RE Magazine, November 2019

Ron Schwartau was speaking to a roomful of co-op leaders, and he could tell “they just weren’t buying it.”

His topic was cooperative governance, and his audience included managers and directors from Uganda’s four electric co-ops.

“You could kind of tell from the body language,’” says Schwartau, NRECA’s Minnesota director and a longtime volunteer with NRECA International. “They were thinking, ‘I don’t agree with this guy at all. We’re going to do it the Ugandan way.’”

In this part of his presentation, Schwartau was specifically taking issue with a Ugandan custom that allows board members to dictate a general manager’s hiring and firing decisions.

“We told them it’s against our co-op practice for the board to interject itself into those decisions,” he says. “But it’s going to take time for them to sort it out. Lecturing people seldom works. We just share our experiences.”

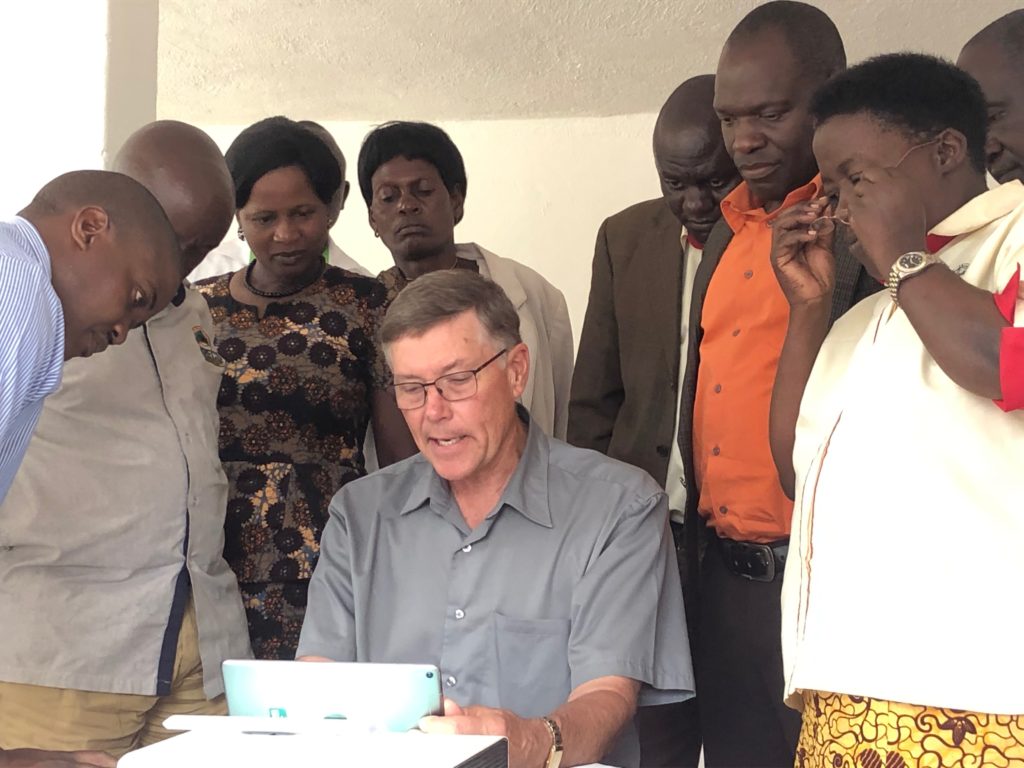

Since late2018, Schwartau, who’s also board president of Nobles Cooperative Electric in Worthington, Minnesota, has been traveling to Uganda with Chuck Dawsey, also a longtime International volunteer and consultant, a 40-year co-op veteran, and a former NRECA director. Their trips are part of a program funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development to share governance expertise with Uganda’s young co-ops, which serve about 30,000 households and range in age from seven to 13 years.

Schwartau and Dawsey say the hiring/firing anecdote underscores a common challenge NRECA International volunteers and staff face: how to deliver a strong message on governance while being respectful of deep cultural differences.

“In the U.S., the idea of the board being involved in the hiring and firing decisions for cooperative employees, other than the general manager, would be a totally unacceptable practice,” says Dawsey, a former CEO of Benton Rural Electric Association in Prosser, Washington. “We’d say that’s board overreach. But, in Uganda, there are strong tribal associations, and they believe that nine board members can be more objective and fairer than one manager about which members of the community to hire.

“We tell them what we do and why we do it, and then it’s up to them to make their own decisions. We’re not there to tell them how to do their job.”

Schwartau says nevertheless, NRECA International representatives don’t shy from consistently emphasizing governance and management principles. He says one way he’s found to break through cultural barriers is to offer lessons that draw on some of the governance and leadership mistakes made over the years by American co-ops.

“We’re not perfect, and it gives us more credibility to admit that we’re not,” he says. “We always tell them, ‘We’re just trying to help you learn from our mistakes.’”

An important part of what we do

In December 2018, the two-man team traveled to the Ugandan capital Kampala to deliver two days of governance training to nearly 40 co-op directors and managers. Topics rangedfrom hiring co-op CEOs to evaluating a co-op’s performance.

They returned in July of this year, visiting each of the four Ugandan co-ops at their headquarters to review their progress and attend their board meetings.

The program grew out of an NRECA International assessment conducted in July 2018 by Dawsey and Garry Mbiad, former general manager of Guernsey-Muskingum Electric Cooperative in Ohio. The assessment report found a need for training and strengthening in a number of areas.

Findings were presented at a workshop of Ugandan co-op and government leaders in September 2018, and Uganda’s Rural Electrification Agency (REA) decided that governance training should be the first priority, says David Gibson, senior engineer and NRECA International’s country director in Uganda.

Future work will include lineworker safety training and materials management.

The training is just one part of NRECA International’s work in Uganda, which began in 2010 and has included developing electrification master plans for all 13 of the country’s electric service territories. Those plans are being deployed and rely on both grid expansion work and the development of mini-grids, Gibson says.

Uganda has enjoyed political stability and economic growth since decades of internal strife ended in the mid-1980s, according to the U.S. Department of State. The department notes that potential challenges include “explosive population growth” and “power and infrastructure constraints.”

Only about 16 percent of Ugandans have access to electricity, and that drops to 10 percent in the country’s most remote areas. The government’s goal is to push the rural electrification rate to 26 percent by 2022 and electrify the whole country by 2040.

“We’ve been committed to helping the Ugandan government with their rural electrification efforts for years, and Ron and Chuck’s work is an important part of what we do,” says NRECA Senior Vice President for International Dan Waddle. “Establishing an electric co-op is difficult, and making sure it lasts is the hardest part. We want to do all we can to give these co-ops the knowledge and tools they need to benefit the communities they serve, which will help put Uganda on the right path toward universal access.”

A great start

When Dawsey and Schwartau returned to Uganda in July, they were pleased to find that two of the co-ops had adopted an important operational tenet and one that is well known to U.S. co-ops: key performance indicators. The co-ops are now collecting data to track progress in areas like total revenue per kilowatt-hour sold and energy losses as a percentage of purchases.

“Two of the four co-ops performed well and picked key performance areas for monitoring, developed performance goals, and created action plans,” Dawsey says. “It’s a great start. We’re hoping they’ll continue their efforts and at the same time inspire the other two cooperatives to do the same.”

Wilson Nyabutundu, senior rural electric cooperative development officer for the Uganda Rural Electrification Agency, says he heard positive feedback from co-op directors and managers about Dawsey and Schwartau’s training.

“Some of the directors and managers were getting this kind of training for the first time, particularly from such experienced consultants—Chuck and Ron—who have had hands-on experience in electric co-ops for a number of years,” he says.

One major change that resulted from the training: Co-op managers have begun preparing and providing board information packets to directors before meetings instead of just as the meeting starts.

“The U.S. co-ops have been in the utility business for over 50 years and have put in place what it takes for successful operations,” Nyabutundu says. “The Ugandan co-ops look to them for best business practices.”

Compounded challenges

Schwartau and Dawsey have also recommended that Uganda’s co-ops work to create a national association of cooperatives as a platform to share information, expertise, and equipment and gain political clout to lobby for resources.

“The board of directors and the managers of the utilities see the value of working together and are excited about the idea,” Dawsey says.

He says having a way to share knowledge and equipment is especially important since the Ugandan cooperatives operate without much of the basic gear, training, and financial resources U.S. co-ops take for granted.

Lineworkers, for instance, rely on motorcycles as their main work vehicles. Each co-op generally has only one pickup truck, and none has a truck big enough to transport poles, which means they have to rent flat-beds from entities in their local communities. Only one co-op has a truck with a crane for heavy construction.

There are also no large truck-mounted augers, so holes are dug by hand. Wooden poles are often not adequately dried or treated to protect them from termites, and they frequently rot and deteriorate in as little as five years, Dawsey says.

There is no formal training program to prepare prospective lineworkers to work around high-voltage lines, and there is not enough personal protective equipment—including hard hats—for all lineworkers.

Compounding these problems is the fact that co-ops don’t have the legal authority to raise rates to pay for new equipment, crucial maintenance, or training.

“I personally don’t believe there is a board or a management team in the U.S. that could efficiently operate under those constraints,” Dawsey says. “I’m just so impressed with the innovation, resiliency, and resourcefulness of these boards, managers, and employees. Even under the worst resource constraints, extremely difficult operating conditions, and very limited financial resources, the cooperative spirit shines through. They just do what they can with what they’ve got. They’re incredibly dedicated.”

Keys to growth and success

The NRECA International training helped Charles Matovu, general manager of the Kyegegwa Rural Electricity Cooperative Society (KRECS), focus on what it will take to help his co-op grow: Set clear and achievable goals and regularly review performance.

“And those targets should not be one man’s development but should be developed in a team manner, including junior staff and board of directors, so that they are owned by everyone,” Matovu says. “Secondly, I learned that however good, understanding, and so on that the management team is, without an effective board of directors team, the rate of growth of our co-op will remain slow.”

The NRECA International team has developed a list of recommendations to help the Ugandan co-ops succeed. Among the most pressing is the REA’s creating a lineworker training center to help crews develop practical skills and safe practices, including climbing techniques, pole-top rescue, clearing outages, performing CPR, and the proper care and use of switch sticks and personal protective equipment.

“This is an immediate and extremely important need that must be addressed,” the 2018 report concludes.

Another recommendation calls for the creation of a central power pole treatment facility with a kiln to facilitate better absorption of wood preservatives.

Ultimately, the cash-strapped, fledgling co-ops should be allowed to charge rates that reflect prospective costs for operations and maintenance, including the higher cost of providing service in sparsely populated areas, the recommendations say.

The report takes on greater urgency as Uganda’s co-ops face growth that is projected to bring 170,000 new households to serve in the next decade, NRECA International’s Gibson says.

“One of the drivers for the cooperative strengthening program is to equip them to handle such a large increase in the size of their networks,” he says.

In the meantime, Schwartau says he hopes the governance training that he and Dawsey provided will help the co-ops operate more efficiently.

“Considering the uphill challenges they face in electrifying the rural areas of the country, we know it can aid them in keeping on course,” he says. “I would hope that, going forward, these cooperatives will reach out to us with more questions and suggestions on helping them succeed.”